Maracatu Rural

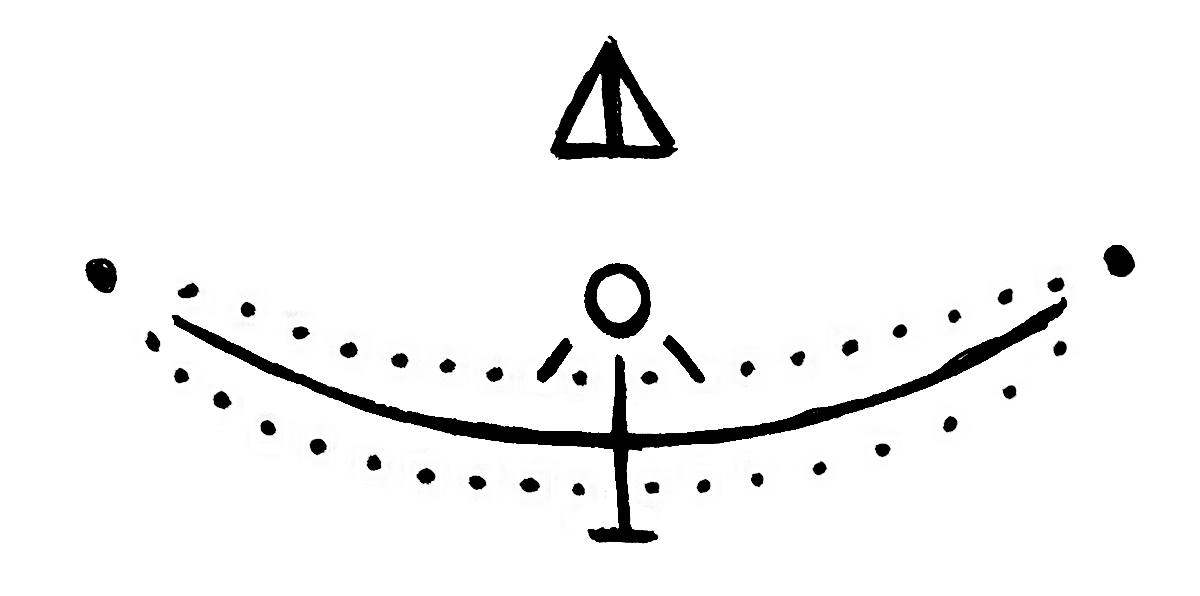

Agile feet amongst the dirt and dust, colorful ribbons and twirls. Mouths hold white carnations that won’t drop even during the most daring moves – a sign of balance. On their hands, a spear to protect the air ; on their heads, shimmering threads emulate the movement of cane plantations in Pernambuco’s Zona da Mata. The arrival of a caboclo is an unexplainable and unforgettable scene.

“It’s an arrival with the Cambinda,

it is Rural Maracatu”

Sambada by Master Anderson Silva

They carry a surrão tied to each of their backs, adorned with sequins and feathers sewn by sugarcane harvesting hands, an instrument that rings about the villages’ streets. Cablocos de Lança are figures resembling enchanted angels, who announce afternoons and evenings of play. By their side, stands another figure: Caboclo de Pena.This one carries a feathered headpiece and an outfit that reminds people this is a festivity deriving from the meeting of Indigenous and Black inhabitants of Pernambuco state.

If Maracatu Nations are Candomblé spilling out over Recife starting at the beginning of the 18th century, Rural Maracatu is its expansion throughout the state, starting a century later. The hands of so many sugarcane plantation workers also brought their black kings and queens along, Damas do Paço and Calungas and their magic.

At the new location, they also learned to play the trombone, the saxophone and the clarinet ; they learned to blow them differently to the orchestras: a new beat, Baque Solto. Xangô’s royalty met with Boi-Bumbá on one of those small-town paths: this is why the images of Catirina and Mateus, two of the characters in Boi-Bumbá stories, often open the way for the processions of this new beat. The couple invites sugarcane plantation workers to take a break from reality.

“Rural Maracatu was originated in the sugarcane plantation.

Only those who are part of a group know the magic of this rhythm”

Master Anderson Silva

The festivities took place in the sugarcane plantation to celebrate the conclusion of long days of farm work. This is where Rural Maracatu was born, light and colorful: the fantasy served as sustenance for daily life. Engenho do Cumbe, a sugarcane plantation, is where the Cambinda Brasileira was first celebrated in 1918: probably the most ancient of all Rural Maracatus. While rehearsing for Carnaval in 2015, amounting to ninety-seven years of existence, this Cambinda were already planing the party for its centennial birthday.

Among fantastic caboclos and playful participants wearing shirts printed with local beauty, the masters’ voices echo musical verses: these are the sambadas, competitions that can last uninterrupted for several nights. If Cambinda Brasileira is the most ancient Maracatu style in the rural area or Pernambuco’s Zona da Mata, the voice representing it that year was the youngest ever: at 19 years of age, Master Anderson Silva impressed attendees for his ability with words and rhythms. Oral literature of this sort cannot be learned in books, nor at college: it takes many years of listening to older relatives singing!

“What a beautiful thing it is to see the Cambinda and its crowded terreiro.

Wherever I sing, there’s poetry in the air”

Sambada by Master Anderson Silva

Poetry in the voices, poetry in the dances, poetry in the hands: all twenty-one Maracatu groups in the city of Nazaré da Mata and surrounding region meet in their warehouses for months on end to make each of the embroideries that shine under the February sunlight. These are festivities whose history goes way beyond Carnival…

Among those is Coração Nazareno, the first women-only Maracatu in the world, formed by women tired of just working in warehouses and not coming out to play. In 2004, the girls at Anuman (Women’s Association of Nazaré da Mata) decided they would found their own baque, where they are Kings, Queens, Masters, Caboclos, Catirinas, and Mateus in their own right.

Be it all-women’s groups, centennial Cambindas, or young artists of daily life: each year, Maracatu groups meet at Nazaré da Mata to perform. They parade and display the meetings of black and indigenous peoples, kings with sunburnt skin wrinkling into a smile. They dance to greet local residents in their homes wherever they go, and drop to the ground when their surrão stop playing. The spells cast by their Mães de Santo cause them to kneel before the churches.

Bead by bead, golden strands hang from the helmets that are tended to throughout the year. In a landscape painted by working hands, Maracatus magically draw while allowing some play: they blur the frontiers between the real and the invisible, and write the possibility of dreaming into the minds of children.