Círio de Nazaré

12:17

Círio de Nazaré. Procession. Catholicism. Fafá and Gaby. Belém. Pará state. Amazon. October. 2 million people

Círio de Nazaré

Street-river-motorcycle-square-mass-street: the image of the Queen of the Amazon carried on foot for more than fifteen days along routes in Belém and its surroundings. The city, known for the jungle delicacies displayed in stands at Ver-O-Peso market, becomes a river that flows in one direction: that of the Saint. Two million people come to blend in with the backdrop unfolding into the Guamá and Maguari neighborhoods in the horizon: accents trying and pronouncing Tucupi, Tacacá, Açaí, Taperebá. Sounds of clapping hands, cries, litanies, and marching bands, a melody that sounds like Pará state itself: abundant exuberance in everything, altogether.

“It’s like our calendar year starts with Círio.”

Gaby Amarantos

While a visitor might not understand much in their first year of pilgrimage, for the Belém natural, Círio is sacred even when it’s merely profane. It’s a time to renew faith in oneself, in one’s family, in one’s culture. Many choose to visit relatives during Círio instead of December, for Christmas. The family meal on the second Sunday of October is also a ritual: spirituality and maniçoba recipes are passed down the generations. The thing is: in Pará state, flavour and knowledge are nearly synonyms. And for the people in Pará, the Catholic Saint feels close enough to have a nickname, Nazica.

The table is set and the house is full, the TV is on and loud, playing the departure from the Saint from the Cathedral towards the square, an older relative recalls: in 1700, a caboclo by the name of Plácido found the tiny image of Senhora de Nazaré at Igarapé Murutucú. The caboclo brought the image to his cottage, mas the Saint would always find its way back to the place where it was found: that is where the caboclo built his chapel, now the Basílica Santuário de Belém do Pará (Sanctuary Basilica at Belém in Pará). Ninety-two years later, the Vatican issued permission for the first procession in honor to the Virgin, a celebration that now is part of Brazil’s intangible heritage.

That previous Friday, a replica of the image found by Plácido gave way to the pilgrimage: the original, as the story goes, cannot be moved from its place. It leaves from the Basilica towards the town of Ananindeua where it spends the night in vigil. At 5am, there’s a mass and it leaves in a convoyed pilgrimage towards the town of Icoaraci. In its own ornate support structure, the carriage, Nazica makes its way through the city until approximately 9am. Since this is an Amazon Saint, the route resumes by boat: so the Círio das Águas (Water Círio) begins, a fluvial pilgrimage. Once at the pier in Belém, a vast amount of motorcycles await with hot engines, noises, and honking: motorbike-pilgrimage is an invention from Pará, a practice that allows more people to follow their patroness.

On Saturday night, after another mass in honor of the Saint, the Transfer takes place: fireworks blend in with the lights from the lit candles, the círios. On Sunday, Belém wakes up to the largest Catholic procession in the world. Tourists join the children of the land for more than two miles of walking: stages with performances by some of the main artists in the region carry the chants for the pilgrims and the image of the Queen, with blessings at each stop.

“For there will be mystery now and forever

No explanation can really explain

It’s much more than seeing a sea of people

Celebrating in the streets of Belém.”

Ave Maria, a song at the Círio processions and masses

There are more than twelve days of masses, prayers, meetings, and parties. Promise keepers come in, paying their dues with knees to the ground, crosses on their backs, flowers, and objects to show their gratitude to Our Lady for the granted graces.

Throughout the path: hands try to come closer. When it’s time for Nazica to arrive, everyone wants to see the image. Raising it to the skies is a constant gesture of respect, veneration. Feet must be agile and resilient to endure all the walking, which many do barefoot as a show of humility and caution: for those who want to come closer to Nazica, it’s best to avoid stepping and hurting those who walk by their side. It’s a metaphor for life, this march.

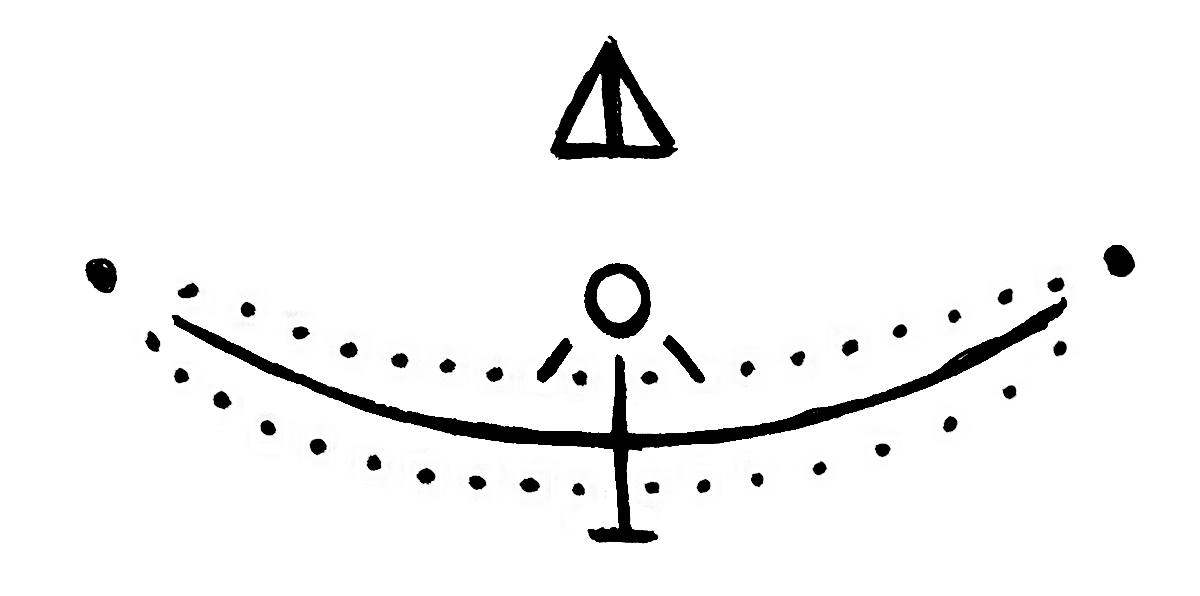

Early in the tradition, in one of the processions, the Saint got stuck in this city, which is more like a river rather than streets. A rope was used to rescue the image and, this time, a group of people reenacted the gesture made by Plácido, the caboclo. Since the dominating culture is one of abundance, every story in Pará multiplies: each year, this tug of war grows and grows, with more people join in to show their efforts toward keeping this faith on the move.

“Every year I am lucky enough to get a piece of the rope.”

Gaby Amarantos

Holding on to the rope is an energy ritual that fortifies the soul: now this year will turn out well, open paths by Nazica, who will always provide! When Sunday fades away and the main procession comes to an end, the worshippers cut the rope into pieces, blessed with the sweat from the believers. As mostly anything in the Amazon, the rope becomes an enchanted object and lucky charm along its path. It’s a gift to fellow citizens and countrymen who need protection, for everyone who knows what it’s like to carry a food-filled cooler on their shoulders upon leaving those shores. Much like a scented bath, it’s a remedy for any troubles of the faith. It’s a riverside story sang by an old caboclo, those that leave you missing a place, eager to return.

interview

Gaby Amarantos

09:26